Libyan Berbers pipe up after decades of forced silence

| Yefren, Libya

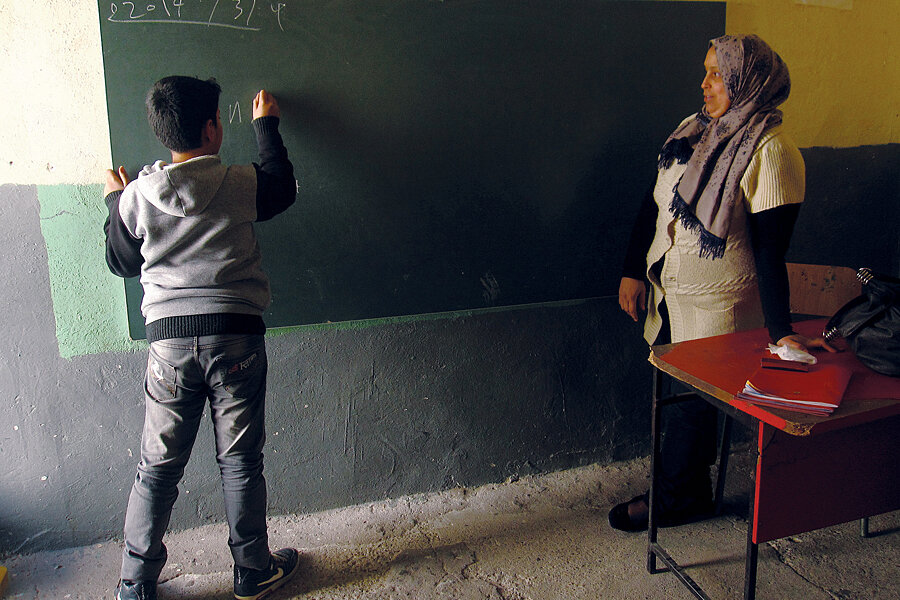

Three times a week Intissar Younes Issa walks over to the Sulaiman Baruni primary school, near her house on the hill above town, and gives lessons that until three years ago would have landed her in jail. One recent morning she taught her pupils a song:

“Nanna a Nanna, sekker asif n zalla, asif n zalla yeshur s yimtekan d wzemmur,” it begins.

The words are Tamazight, an ancient language banned by Libya’s former dictator, Muammar Qaddafi. In English they mean, “My grandmother, my grandmother, you wake the valley of Zalla, the valley of Zalla filled with figs and olives.”

The song describes the region of Yefren, home to Libya’s Amazigh, or Berber, minority, which includes both Ms. Younes Issa and her pupils. Mr. Qaddafi’s ouster has allowed them to bring their language into the open and launched a debate over minority rights as Libya struggles to remake itself.

Rich history repressed

Amazighs have inhabited North Africa since before recorded history; the earliest known reference to them may be 1st millennium BC rock engravings of chariots in the Sahara. Romans, Vandals, and Byzantines all conquered the region, followed by Arabs, who brought Islam and their language. But Tamazight, a group of dialects distantly related to Arabic, has survived in places like Libya's Nafusa Mountains, a towering arc of red-brown escarpments that swing southwest from Tripoli to the Tunisian border.

Libya’s several hundred thousand Amazighs consider this their cultural heartland, although some towns are Arab. According to Alberto Denti di Pirajno, an Italian colonial doctor posted to Libya in the 1920s, the two populations “cordially disdained” one another.

"The Berbers find the Arabs obtuse, thieving, and treacherous,” he wrote in his memoir, "Un Medico in Africa," "while the Arabs say that the Berbers have ‘the greed of the Jews, the venom of the asp, and the honesty of a prostitute’.”

Upon seizing power in 1969, Qaddafi declared Libya purely Arab. Tamazight was suppressed, Amazigh names were forbidden, and Amazighs’ role in Libya’s history was downplayed in textbooks. For Amazighs, Libya’s 2011 uprising was a chance to reassert their culture.

Amazigh town elders backed revolt in online video statements, including one in both Arabic and Tamazight. As Qaddafi’s shells rained on the mountains, the Tamazight letter “z” – two semicircles bisected by a vertical line, used by Berbers throughout the region – appeared in graffiti as an emblem of identity. Finally it appeared on Tripoli walls as Amazigh rebels helped topple Qaddafi’s regime.

Revival

Amazighs immediately began bringing Tamazight into the public sphere. While most Amazighs continued speaking the language in private during Qaddafi’s rule, not all know how to read and write it. Mrs. Younes Issa was among volunteers who began teaching children Tamazight. In 2102, Amazigh town councils began funding teacher training, salaries, and textbooks.

Last year, Libya’s interim parliament declared Tamazight and other minority languages components of Libyan society and authorized schools to teach them as optional subjects. The education ministry has even begun funding Tamazight instruction.

With liberty has come enthusiasm for perfecting one’s Tamazight, Younes Issa says, chatting with The Christian Science Monitor and fellow teachers in the school director’s office.

“For example, before we would say ‘hammam’ (bathroom), from Arabic, but now people are saying ‘abdus.’ Even ‘cugina’ (kitchen), which comes from Italian (“cucina”); now we say ‘anwal’.”

“We here are the roots,” chimes in Souad Shneb, a large, forthright lady who also teaches at Sulaiman Baruni school. “The roots of Libya.”

Language is only the beginning

For many Amazighs, basic freedom of expression isn’t enough. They also want Libya’s future constitution to enshrine Tamazight as an official language and guarantee its protection.

Last November Amazigh protesters shut down an oil port near Tripoli to press those demands. And last month the High Amazigh Council, an activist umbrella group, called on Amazighs to boycott constitutional drafting committee elections, arguing that the two seats reserved for Amazighs from a planned 60 were insufficient.

“There’s an Arab nationalist thinking that rejects us,” says council member Nuri Ali Sherwi, who was among 45 Amazigh activists he says were jailed in the 1980s after they organized to promote their culture. “We won’t recognize a constitution that doesn’t recognize us.”

But others worry that identity politics risk inflaming tensions at a time when Libya’s government is weak and militias proliferate. Magazine editor Salah Ngab makes a point of running content in Tamazight, Arabic, English, and the Taduga language of minority Tebus in his monthly magazine, “Aramat” (“Equinox”).

“The aim is to send a message to our people that it’s possible to be different and live in peace,” Mr. Ngab says.

Back in Yefren, Amazighs such as local radio director Ashraf Amroushi are relishing new freedoms. During the 2011 war, Mr. Amroushi found himself holding a gun with other rebels. Now he oversees the broadcast of Tamazight news bulletins, live discussions, and especially, music.

“I feel that now I’m offering something that’s even better than what I offered in the revolution,” Mr. Amroushi says.